On the sidelines of the G20 Summit in 2023, the leaders of India, Saudi Arabia, France, Italy, Germany, the UAE, the US and the EU committed to work together and establish the India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor or IMEC. The corridor was expected to stimulate economic integration between Asia, the Arabian Gulf, and Europe.

The world in 2023 was different in many ways—geopolitically and geoeconomically. There was an unprecedented interest in mutual growth through interdependence. Newer ways of international cooperation were being forged through regional groupings, accords, and mutual understandings.

Wars in Ukraine and the Middle East, the Red Sea crisis, and reductions in the capacity of the Panama Canal were yet to overshadow initiatives like the IMEC. Joining each other with clear intentions and clean drawing boards was all that was required. The world was focused more on geoeconomical initiatives such as the Quad, the Abraham Accords, G20, and I2U2 than geopolitics.

Against this backdrop, last week’s India-US joint statement, and its 36 paragraphs covering defence, trade and investment, energy security, technology, multilateral cooperation and people-to-people cooperation, assumes major significance. Paragraph 28, under ‘Multilateral Cooperation’, highlights the importance of investing in critical infrastructure and economic corridors.

“The leaders [US President Donald Trump and Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi] plan to convene partners from the India-Middle East-Europe Corridor and the I2U2 Group within the next six months in order to announce new initiatives in 2025,” read the statement.

Most importantly, the joint statement validates the memorandum of understanding (MoU) for the IMEC and reaffirms that the initiative has the continued support of India and the US. It will be taken forward, albeit under a very different and challenging geopolitical scenario in the Middle East in 2025.

Alternative economic corridors

Transport connectivity and economic corridors like the IMEC enable and integrate spatially separated regions for trade and commerce, mutual benefits, and shared prosperity across borders. For international trade beyond traditional sea routes, countries are building newer highways, railroads, under-sea tunnels, and aviation hubs connecting regions and continents.

East Asia has already been connected with Europe and Central Asia through an efficient railroad network, with Chinese cargo container trains frequenting the Northeast Asia–Europe–Central Asia route. Other established and upcoming connectivity projects worldwide include the GCC rail link project; India’s road and rail network with Southeast Asia; the International North-South Corridor connecting Russia, Iran, and India; the Pakistan-Iran-Turkey container train corridor; and the African Union’s ambitious plan for a North to South Africa rail line.

The post-Covid resurgent world sought newer connectivity options, including multimodal transport across continents and alternate trade corridors. However, by the end of 2023, the Red Sea crisis had severely impacted international shipping across the Suez Canal, a lifeline for Asia-Europe trade. The war in Ukraine had started impacting movement across the Northern Corridor while the drought in Lake Gatun—the water source that makes the Panama Canal navigable—adversely affected ships transiting the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans.

A much longer diversion via the Cape of Good Hope, as an alternative to the Suez Canal, and another via Cape Horn, as an alternative to the Panama Canal, caused immense distress to shipping lines. Logistics costs and transit times increased manifold.

The time has come for countries to come together and look for alternate economic corridors and multimodal linkages for transcontinental connectivity. In this context, whether the IMEC is the best option available needs a comparative analysis.

Also read: India-US ties stuck in cute acronyms. Delhi must wait out the chaos

A brief geography of IMEC

The idea of the IMEC has its roots in the Abraham Accords—signed on 15 September 2020, between the US, Israel, the UAE, and Bahrain—followed by the Indo-Abrahamic Accord and, more formally, I2U2, formed in October 2021 by India, Israel, the US, and the UAE.

Interestingly, the MoU for the IMEC, signed in 2023, did not include Israel and Jordan—two crucial countries for the corridor. Further, I2U2 is looking at expanding the group to include Saudi Arabia and other concerned nations. Formal agreement for the IMEC by all stakeholders is therefore crucial to decide future modalities.

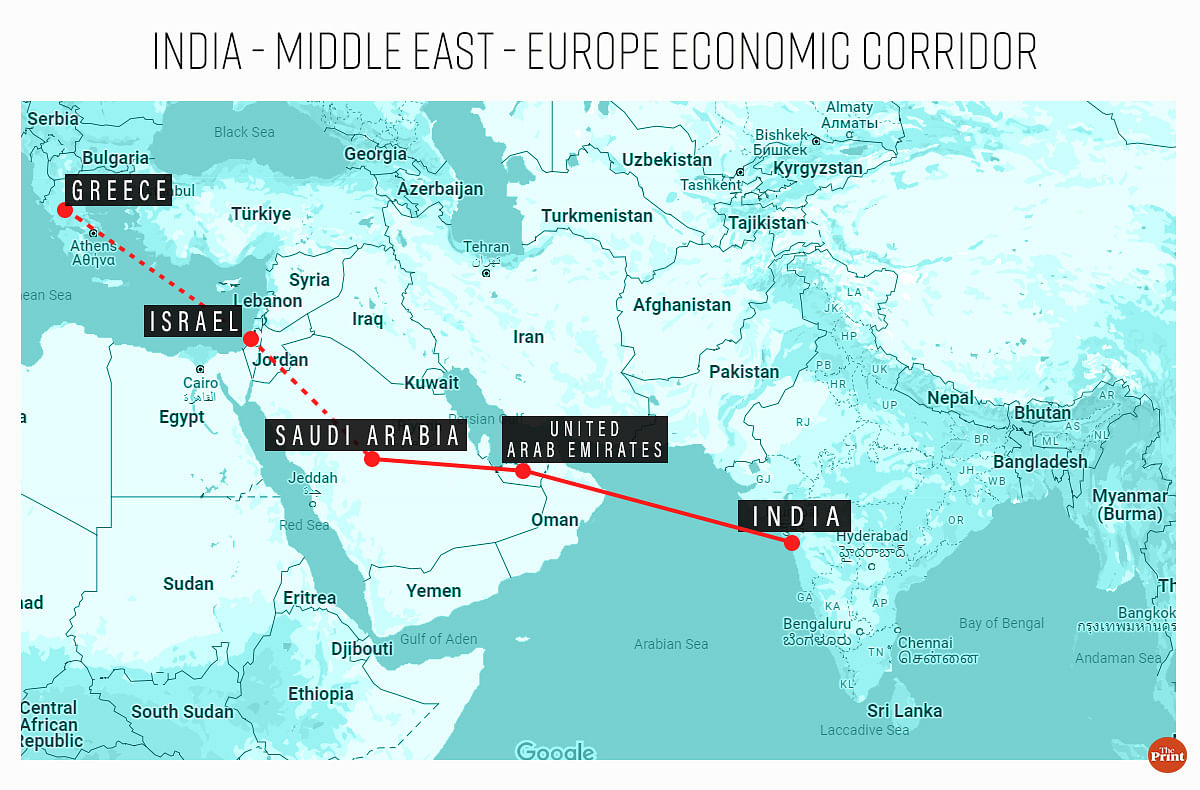

The recent joint statement mentions both the IMEC and I2U2 together. There is a broad understanding that the IMEC will be a sea-land-sea corridor connecting India, the Middle East, and Europe. This multimodal corridor has three major segments. The first is the sea link between western Indian ports and the ports of the UAE, Oman, and Saudi Arabia. The second segment is rail connectivity for the transhipped cargo from Gulf ports to the Port of Haifa in Israel. The third segment is sea connectivity across the Mediterranean between the Port of Haifa and European ports.

The transshipment of cargo, both containerised and bulk, would be required at both ends of rail links. The land movement is envisaged by freight trains of the GCC network from Gulf ports, onward by Saudi Arabia Railways, the Hedjaz Jordan Railway, and the Israeli rail network to the Port of Haifa.

India’s western ports—Mundra, Kandla, JNPT, Vizhinjam, and Vallarpadam—already handle containerised and other international cargo, with growing capacities. The ports in the UAE (Jebel Ali), Oman (Salalah and Duqm), and Saudi Arabia (Ras Al-Khair and Dammam) also have adequate handling capacities.

The GCC rail network connecting these ports is getting commissioned in stretches. However, this needs to be linked to the Saudi rail network, which has an efficient heavy haul rail link up to Al-Haditha, at the border of Jordan. From there, a missing rail link of about 260 km, when commissioned, will run across Jordan and connect to Beit Shean in Israel, which is connected to the Haifa port.

Haifa is the biggest port being operated by the Indian APSEZ (Adani Ports and Special Economic Zone). It is geared up to carry the potential traffic of the IMEC to and from major European ports including Piraeus in Greece, Trieste in Italy, and Marseilles in France. Onward movement of cargo to destinations will be undertaken by a well-laid-out rail and road network.

While the GCC rail network is being connected to Saudi Arabia Railways, Jordan and Israel will have to undertake the construction of short stretches of new rail lines on their respective networks. These will have to be at par with the Saudi rail network to enable seamless movement of cargo from Gulf ports to Haifa.

The national priorities, however, now depend more on geopolitics than on purely economic considerations. Israel and Jordan will likely look for financial models for this cost–intensive project. The priority should be to put in place an early agreement among the IMEC countries, including Israel and Jordan, incorporating all issues.

Also read: Encourage IIT, IIM graduates to work in smaller towns. Decongest big cities like US, Japan, Spain do

A historic opportunity

Whether the IMEC is the best way forward, and why an alternate corridor is necessary, are questions to be considered in light of the adverse impact of the Red Sea crisis. A UNCTAD (UN Trade and Development) Rapid Assessment Report covering the most crucial period of the Red Sea Crisis stated that by February 2024, container tonnage crossing the Suez fell by 82 per cent. Between December 2023 and February 2024, the overall ship tonnage entering the Gulf of Aden fell by more than 70 per cent.

Consequentially, the vessel tonnage passing the Cape of Good Hope increased by 85 per cent, as compared to December 2023. This also caused freight rates and transit time to increase manifold—the diverted route via the Cape of Good Hope also caused an avoidable 70 per cent increase in greenhouse gas emissions. Global trade cannot sustain this kind of prolonged adverse impact, so alternatives like the IMEC assume significance.

The revival of an old Israeli project, the Ben Gurion Canal, is being considered an alternative to the Suez Canal. The proposed canal also connects the Red Sea with the Mediterranean. Project details indicate that it will run from the Gulf of Aqaba via the port city of Eilat, passing through Arabah Valley for about 100 km North. Thereafter, it will take a westward turn north of the Gaza Strip, connecting to the Mediterranean.

Estimated to be about 257 km long, it will be shorter than the Suez Canal and may be built with a deeper draft to enable the transit of larger ships. The major constraint would, however, be its Red Sea transit and the uncertain passage through the Bab al-Mandab strait.

Another possible rail route from the Indian subcontinent via Iran and Turkey would involve the construction of a heavy haul freight rail network. The present rail network between Tehran and Istanbul is not available in stretches, especially to bypass Lake Tatvan, which necessitates ferry crossing of rail coaches. This longer route with a change of gauges also lacks connectivity to major seaports. Moreover, the major traffic flows to and from the Arabian Gulf cannot use this route.

In view of the above, the IMEC could well be the most efficient alternative to the Suez Canal. It has the potential to not only cater to India–Europe trade but also serve the larger Middle Eastern markets of Jordan, Syria, and Iraq.

Incidentally, many alternate routes and corridors are being proposed and commissioned in different regions. This includes the Middle Corridor, a rail-sea-rail corridor from Central Asia to Europe via the Caspian Sea, and an interoceanic corridor in Mexico, which provides rail bridging between the Atlantic and the Pacific Oceans.

Of late, the Panama Canal had to cut down its daily transit by about one-third due to low levels of water at Lake Gatun. The upcoming interoceanic corridor will cut through the narrowest part of southern Mexico, connecting Veracruz on the Atlantic coast to Oaxaca on the Pacific coast, thus becoming a crucial alternative to the Panama Canal.

Using the IMEC as an alternative to the Suez Canal or as a more efficient corridor is a historic geoeconomic and geopolitical opportunity. Even as the context around it evolves rapidly, the India-US joint statement strikes the right note and will prove critical for the way forward.

Mohammad Jamshed is a Distinguished Fellow at CRF. Views are personal.

(Edited by Prasanna Bachchhav)